We can never extract all of a mineral from the earth but we can extract all of the ore that is easy to extract and end up with progressively less yield. Minerals "run out" when they become so rare and expensive that they can no longer be used in their previous roles.

The amount of a mineral remaining in the ground and the ease of extraction will affect its price and as the price rises other materials will be substituted. These substituted materials will then also be in danger of running out. Whether the consequences of resource depletion are dire or not depends upon ingenuity of substitution and whether there are serious dislocations as substitution occurs.

The chart below shows the adequacy of current reserves of most commercial minerals. The adequacy is how long the known reserves will last at current rates of production.

The chart has a logarithmic adequacy scale. According to this chart Indium should now be in the region where its price will escalate rapidly. Has this happened?

it probably has happened, indium is now six times the price in 1994 and the price is very volatile. Indium production, although initially responding to this price rise has stuck at about 600 tonnes per annum. (US Geological Survey). The comment in the US Geological Survey: Mineral Commodity Summaries 2011 is that "Indium’s recent price volatility and various supply concerns associated with the metal have accelerated the development of ITO (Indium Tin Oxide) substitutes. Antimony tin oxide coatings, which are deposited by an ink-jetting process, have been developed as an alternative to ITO ...".

Antimony has a 10-15 year adequacy at current consumption rates - using it as a substitute for indium will reduce this period. So once one rare metal fails there is likely to be increased pressure on substitutes.

In general the price of almost all metals has increased by about 400% since 1994 which suggests that demand is outstripping supply. The demand is largely in China which takes over half of the world's supply of many metals. Were the metal ores freely available it would be expected that the global prices would rapidly adjust downwards.

Until 2001 the price of metals fell year on year suggesting increasing availability:

Unfortunately it is in the nature of growth curves that everything can be growing apace in one decade then the curve can collapse in the next so the crucial data lies between 2000 and the present day. The curves look rather different for recent years:

If the recent price changes are due to shortages rather than a simple excess of demand then there should have been a less than expected increase in the supply of lead as the price increased. The production of lead did not increase much at all in response to the elevated prices in 2005-2007, US production was particularly refactory:

Something might be going wrong with the ease of production of lead. We are coming to the end of easily extractable lead but iron ore is abundant. Iron ore production responded to prices in the expected fashion:

If ore extraction becomes more difficult then more energy is needed in the extraction process. There is a feedback between oil prices and ore extraction costs. A computer model such as that used in Limits to Growth would be needed to model the complex interactions of energy and metal prices.

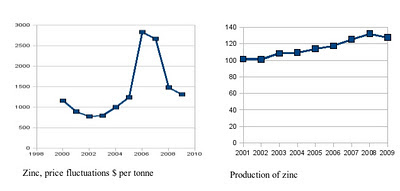

The production of zinc, another metal, like lead, that is near to its limits, is also strangely detached from the current price:

World gold production is also independent of price at about 2500 tonnes a year. However, before accepting that the decoupling of production from price indicates that a mineral is "running out", it should be borne in mind that the production of vanadium was fairly steady at about 50,000 tonnes from 2000-2009 despite large price fluctuations from around $5000 a tonne in 2002 to $38500 a tonne in 2008. Yet there are massive reserves of vanadium. However, vanadium demand has leapt and most pundits blame the price rises on shortages, there being a severe lack of current extraction capacity (reserves) even though there are adequate long term base reserves. So the failure of vanadium production to respond to demand is an exception that proves the rule that refactory production is indicative of shortage. In the case of lead and zinc it makes sense for the mining companies to do a complex balancing act, leaving as much as possible in the ground where it can only increase in value whilst producing sufficient to provide healthy profits.

The analysis shows that the adequacy data in the first chart in this article is credible and that lead, tin, zinc, mercury etc. are indeed effectively running out in the coming decade or so. "Effectively running out" meaning that the price will be high and volatile and production fairly steady or reducing as mining companies start to regard their mines as appreciating assets rather than production facilities.

See also:

The Limits to Growth

Further reading:

Historical statistics for mineral and material commodities in the United States

Scarcity of minerals, metals a concern for manufacturer's suppliers

Mineral reserves are divided into "reserve base", which is all of the mineral currently known to be in the ground and "reserves" which is the part of the base that can be "economically extracted". There is also the "Inferred reserve base" which is a guess at the amount in the ground on the basis of current knowledge.

The amount of a mineral remaining in the ground and the ease of extraction will affect its price and as the price rises other materials will be substituted. These substituted materials will then also be in danger of running out. Whether the consequences of resource depletion are dire or not depends upon ingenuity of substitution and whether there are serious dislocations as substitution occurs.

The chart below shows the adequacy of current reserves of most commercial minerals. The adequacy is how long the known reserves will last at current rates of production.

|

| Global mineral reserves. The red line marks 2012 |

|

| Historical Indium Prices |

Antimony has a 10-15 year adequacy at current consumption rates - using it as a substitute for indium will reduce this period. So once one rare metal fails there is likely to be increased pressure on substitutes.

In general the price of almost all metals has increased by about 400% since 1994 which suggests that demand is outstripping supply. The demand is largely in China which takes over half of the world's supply of many metals. Were the metal ores freely available it would be expected that the global prices would rapidly adjust downwards.

Until 2001 the price of metals fell year on year suggesting increasing availability:

|

| Selected Minerals Prices 1967-2001 |

|

| The Price of Lead 2000-2009 |

|

| Lead Production 2000-2009 |

|

| Iron Ore Production and Price 2000-2009 |

If ore extraction becomes more difficult then more energy is needed in the extraction process. There is a feedback between oil prices and ore extraction costs. A computer model such as that used in Limits to Growth would be needed to model the complex interactions of energy and metal prices.

The production of zinc, another metal, like lead, that is near to its limits, is also strangely detached from the current price:

|

| Zinc Production and Price 2000-2009 |

The analysis shows that the adequacy data in the first chart in this article is credible and that lead, tin, zinc, mercury etc. are indeed effectively running out in the coming decade or so. "Effectively running out" meaning that the price will be high and volatile and production fairly steady or reducing as mining companies start to regard their mines as appreciating assets rather than production facilities.

See also:

The Limits to Growth

Further reading:

Historical statistics for mineral and material commodities in the United States

Scarcity of minerals, metals a concern for manufacturer's suppliers

Mineral reserves are divided into "reserve base", which is all of the mineral currently known to be in the ground and "reserves" which is the part of the base that can be "economically extracted". There is also the "Inferred reserve base" which is a guess at the amount in the ground on the basis of current knowledge.

Comments